《a diner》

work at the Nanzan House in Aichi, JAPAN.

Participatory Installation

size : 75.6㎡ (1,050cm×720cm).

materials : furniture, home appliances, daily necessities(used in my daily life), rain lights, cloth.

11/10/2024.

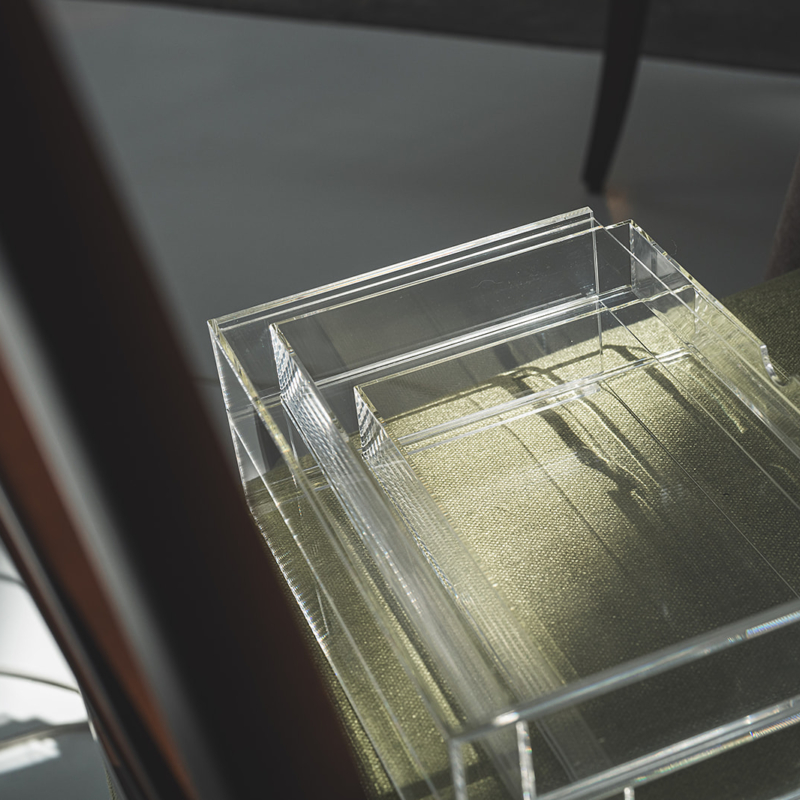

This work was installed inside a chapel at a wedding venue, as part of the artist’s own wedding ceremony, which simultaneously functioned as a site-specific exhibition. The artist recreated a lived domestic environment by bringing in furniture and everyday objects from the shared house where they reside: laundry, cooking tools, a game console, household items. These were not arranged for display, but composed into a space as an embodiment of “relationality embedded in daily life.”

Visitors were asked to take off their shoes and were free to inhabit the space. They could vacuum the floor, fold the laundry, or play games. Rather than “viewing” a work, the experience offered an encounter with the artist’s embodied reality—an immersive contact with life itself.

At the center stood a dining table. Four chairs encircled it, each paired with objects in contrast: a cracked glass with a pristine one, an empty container with one filled to the brim. In a society flooded with competing claims and unresolved tensions, even the most well-intentioned assertions can carry the risk of violence toward others. We are constantly exposed to these frictions. Yet perhaps, in something as ordinary as gathering around a table, we can find a force capable of reconfiguring our own stance—momentarily setting aside ideologies, backgrounds, and polarities—to rediscover a more primal form of relation. This installation functioned as a metaphor for that possibility: a space not only between artwork and viewer, but between presences.

To encounter this work was also to encounter a physical schema (schéma corporel, Merleau-Ponty) sedimented in the artist’s own daily life. The spatial positioning of familiar objects, their use traces, and the rhythms of lived movement formed a tacit language through which the visitor could naturally participate. Through this, the installation held the potential to subtly alter the viewer’s bodily schema. If, upon returning home, one found the view of their own dining table subtly transformed, then the work had fulfilled its significance—not as an object of display, but as a quiet tremor in the texture of everyday life.

Rather than rejecting institutional exhibition formats, this work infiltrates their interior by importing “domestic life” into the frame. It proposes an alternative model of exhibiting—one in which lived experience is not represented but co-created and remembered in real time. In doing so, it invites us to reconsider the very act of presenting a work as a mode of relational practice.